Did you know that the Sutro Library has over 2,000 biographical dictionaries in its collection (such as Who’s Who publications) from all over the United States as well as internationally? These useful sources can help provide the historical context for your ancestor’s life. In this blog post written by one of our volunteers, Ryan Dickson, Ryan explores the kinds of information found in these types of publications. If you are interested in finding these sources at the Sutro Library, try searching the catalog by combining your geographic area of interest (country or state) and the word “biography.” If you need help, feel free to contact us at sutro@library.ca.gov or via the Ask a Librarian service on the California State Library website.

Browsing the book stacks here at Sutro Library I am struck by the plethora of biographical sketches from across the globe and time. As an English professor, these collections spark my interest because they show how print media concretizes the atmosphere of a given era.

One such collection, Men of Hawaii particularly stood out because of its bold black cover and golden embossed lettering shining outwardly. [1]

This reminded me that Edward Said, who coined the word orientalism and wrote a controversial book on the subject, defines it as the process of restructuring another’s land, especially when that reconstructing comes with the heavy hand of colonial bureaucracy. And it is in Men of Hawaii, where editor George F. Nellist focuses his attention on men who have made the Islands a career rather than promoting Hawaiians themselves.

Similar books, Who’s Who in the World for example (4th, 5th, and 7th Editions all in Sutro Library’s Reading Room), include selected individuals as well as those who paid to appear in the collection and wrote their own sketches too. Therefore this collection offers a glimpse into what some of the men of Hawaii thought of themselves, along with a look at who believes that appearing in such a collection is important.

These sketches are part of a longer series also published by Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Ltd., including The Story of Hawaii and Its Builders, which is also housed in the Sutro Library stacks. In its foreword, Riley H. Allen writes that these collections provide a “standard reference work and record of men who deservedly occupy a high place in the industrial and cultural history of the Hawaiian Islands.” [2] This reflects the dominant theme of books published during this time period to take indigenous culture and reframe it on how it relates to the incoming culture.

Further pulling on themes of the early twentieth century, namely the patriarchy, believing males are the only noteworthy gender negates indigenous Hawaiian culture. For example, traditional Hawaiian culture recognizes three genders. The third, mᾱhū, possessing both masculine and feminine qualities, or both kapu and noa behavior roles, and often has a higher spiritual position within the community. Furthermore, in traditional Hawaiian culture, like most traditional cultures pre-Western intervention, gender roles were divided, but none were less important than the other, as they all held importance in the community’s prosperity. [3]

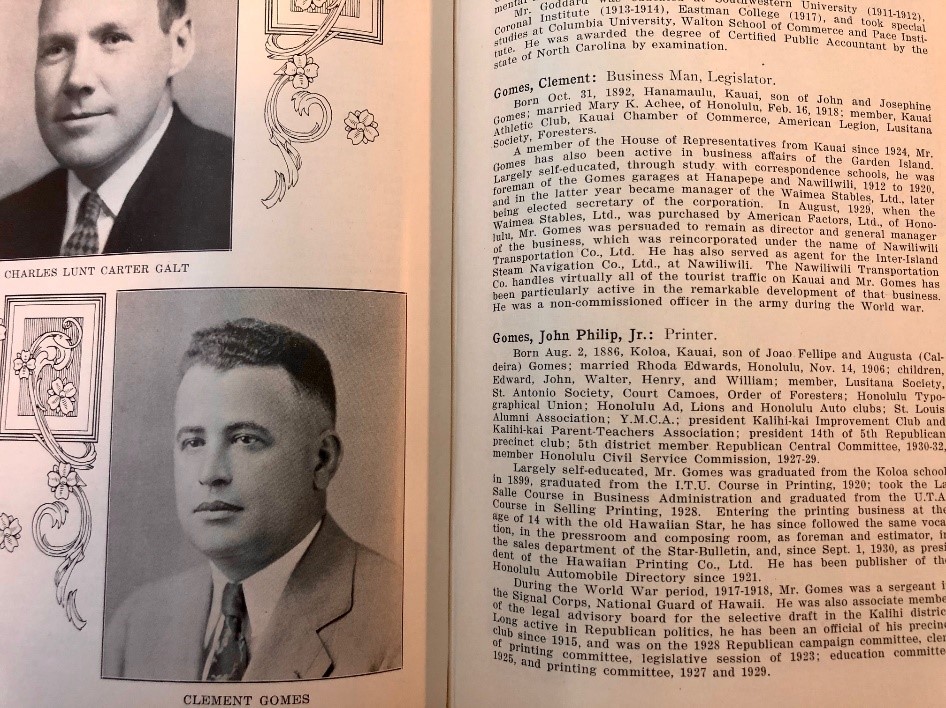

Discounting the fact that this collection of biographical sketches rejects any other genders’ ability to reach achievement within the Islands, Nellist affirms throughout the collection that it is mainly Anglo-Americans, and some Japanese, that are noteworthy. Figuring out what is noteworthy about the men sketched here is perplexing by today’s standards. Without a description in the collection stating what the criteria was for notable achievement or inclusion, we end up with legislators next to printers and we are left wondering why. What does a lawmaker have to do with a person who can produce mass media?

This physical manifestation of those deemed men of achievement defines who has status as a real man in the 1930s. This in turn devalues those men and women who are not included in the collection, namely indigenous Hawaiians.

Since many of the men included are born and educated on mainland America, one wonders what precipitated such a move. Possible it is similar to our current need for housing and a job. Colonization of the Hawaiian Islands offered many opportunities to impose the newcomer’s will on the land and people, as is demonstrated by the professional positions held by the entries. It is particularly the inclusion of educators that catches the readers’ attention.

Much like printing, educators reinforce ideological beliefs for their students to follow, societies prescribed notions of right and wrong, as well as failure and achievement (think grading, for example). One entry, W. Harold Loper, notes that with one year at Harvard post-baccalaureate, Loper became a high school principal for 3 years, then instructed summer sessions at University of Hawaii for a few years in an undisclosed discipline. Although Loper’s achievements seem average by today’s standards, the reader can’t help but wonder why he is still included among the “notable.”

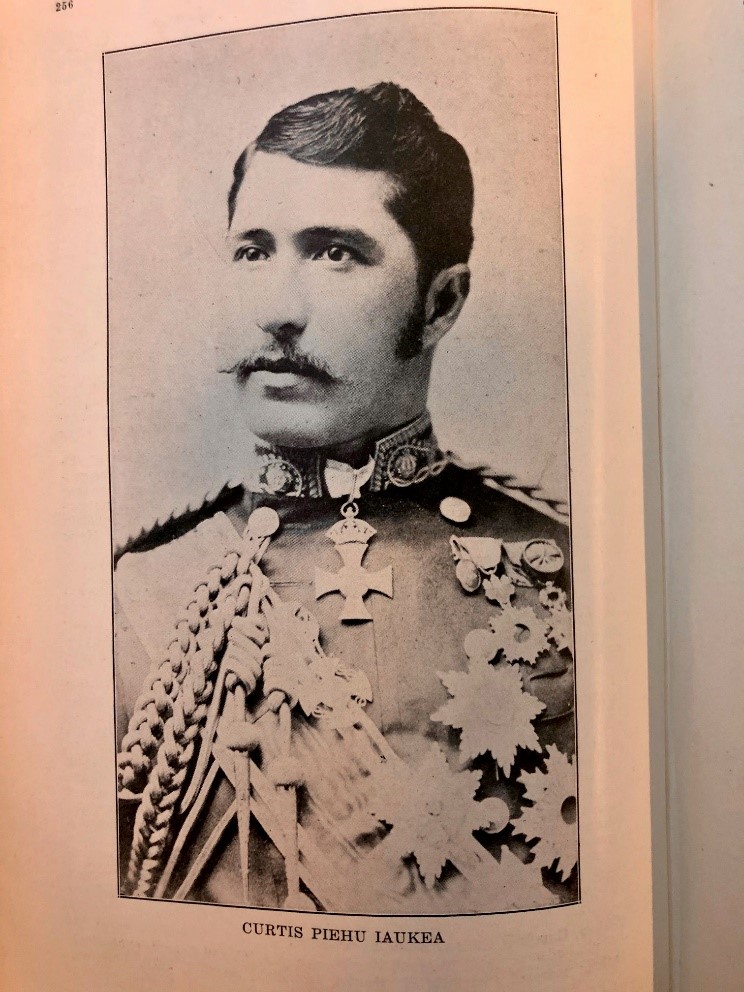

Even when native Hawaiians are included, they are couched in terms of their place in the newcomer’s history. For example, Curtis Piehu Iaukea is given the title Financial Trustee, even though he is “a distinguished survivor of the monarchical era” (emphasis mine). Some of his other achievements include acting as chamberlain for the Hawaiian royals to attend Queen Victoria’s Jubilee and a meeting with President Cleveland. No real mentions of his duties, relationships, or achievements outside the Anglo world is given.

Perhaps it is a misnomer that these are men of achievement. Perhaps these are just men of Hawaii as the title suggests. Or perhaps these are the men whose achievements are sanctified by a certain ideology. Whatever it is, Nellist and The Honolulu Star-Bulletin appear to have promoted achievement based on its proximity to Anglo-American society.

Being surprised that a collection of this sort maintains antiquated hierarchies is a bit naïve. In fact almost any collection that attempts to record achievements, whether they are of men, women, indigenous, or newcomer, will exclude someone. However more than being a record of the inhabitants of the Hawaiian Islands in 1930, Nellist and Men of Hawaii define what achievement looks like…

…and what achievement is willing to encompass.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Men of Hawaii: A biographical record of men of substantial achievement in the Hawaiian Islands, volume 4, edited by George F. Nellist and published by The Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Ltd., in 1930 and first published in 1917.

Call Number: Sutro Library Reading Room DU624.9 M4.

[2] The Story of Hawaii and Its Builders: An historical outline of Hawaii with Biographical sketches of its men of note and substantial achievement, past and present, who have contributed to the progress of the Territory (1925) published by Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Ltd..

Call Number: Sutro Library Reading Room DU624.9 M41.

[3] “Māhū”. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Māhū

I found Sam Kamaka in the Men of Hawaii. The Kamaka ukulele is surely the most famous in the world. As you point out, there is only a pinch of pepper in the whole sea of salt that is this directory. Did people pay to have their bios included in these directories?

Hi Dev, Diana, Jose and Mattie!

Hey Craig!! It’s not clear from this publication, but we suspect that either they paid to be included or the Honolulu Star-Bulletin selected them. I believe books like this with sketches are also called vanity publications. Even if you can’t find your ancestor, you might find someone from their FAN Club (Friends/Family, Associates, Neighbors).

So nice to hear from you!

Dvorah (Dev)